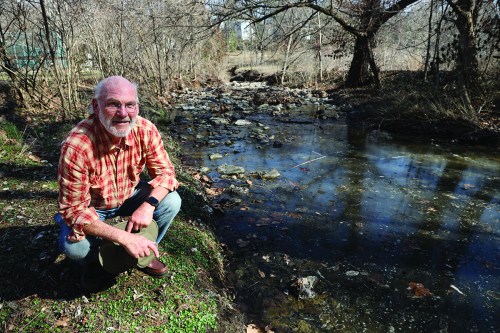

Environmentalist David Wilson, an expert on watersheds and wetlands, surveys Shady Creekin suburban St. Louis. Photo by Ursula Ruhl.

by Jack Farish

The creeks and streams of St. Louis play crucial ecological roles and can provide social and economic benefits to the communities on their banks. Unfortunately, due to intervention, watersheds can be damaged and their natural beauty destroyed. Local watershed expert David Wilson can teach us a lot about watersheds, how they should function, and how we can change our ways to encourage their survival.

Wilson began his academic career as a student of history. As a graduate student, Wilson studied Chinese history at Washington University in St. Louis and had an opportunity to spend two years abroad in Hong Kong.

“It’s a very crowded city,” said Wilson. “When I was there in the 1970s, there were 4 million people living in Hong Kong”

Due to a combination of drought and political tensions in China, Hong Kong was neither able to collect nor trade for the water needed by its growing population.

“They limited the water to four hours a day,” Wilson recounted. “Then they limited it to four hours every two days – that’s all the tap would run. Then it was four hours every four days. If you live in an environment like that, you become very aware of your environment and where your water comes from.”

That awareness grew into a concern for environmental issues. When Wilson returned to St. Louis, he began volunteering, and eventually working for, the Missouri Coalition for the Environment, taking on a variety of different issues. For the last fifteen years, Wilson has worked as a water quality and watersheds specialist with the East-West Gateway Council of Governments – the metropolitan planning organization of greater St. Louis.

In addition to working to address environmental issues directly through these organizations, Wilson has strived to get the word out on issues he is passionate about. He has taught sustainability at Webster University and organized tours of local watersheds.

The first lesson of watersheds is that everyone lives in one, according to Wilson. “A watershed is not the river,” Wilson said. “It’s not the river and the river banks or the floodplains around it. The watershed is everything that drains into the river. Everybody’s in a watershed.”

This means that the responsibility to manage watersheds in an effective and sustainable way falls not only on the communities right along river banks but on all of us. Unfortunately, human-managed watersheds are often far from naturalistic.

“In many developed cities, the rivers and creeks get put into pipes,” Wilson said. “If you look at a watershed map, there are lots of little creeks and streams in Ladue, Webster Groves, and Kirkwood. Once you get to the city you see very few streams because everything has been put underground into pipes.”

Natural watersheds are far more sustainable and provide many benefits to local communities and ecosystems. To begin to understand these benefits one has only to consider the most basic knowledge of earth science: the water cycle.

“During the evaporation process, water is naturally being cleaned,” Wilson said. “Water evaporates any chemicals or impurities that would be hazardous to human health.”

Water in underground pipes isn’t warmed by the heat of the sun, so it doesn’t evaporate as quickly as water on the surface.

Natural watersheds also nourish an abundance of plants, which in turn provide food and shelter for local wildlife. Additionally, an amply-planted landscape soaks rainwater deep into its roots, replenishing the watershed’s supply of groundwater – a crucial element of watersheds. As this water is filtered through roots and soil it is naturally cleaned of particulate debris before being discharged into streams.

“A lot of rivers that you see are not only taking water from rain but are also fed by clean groundwater that seeps in,” Wilson said.

Streams in human-managed watersheds tend to dry up fast. Since these streams don’t have the same steady supply of groundwater that would be present in a natural watershed system they rely on heavy rains to fill up.

The water that does collect in human-managed streams then runs quickly downhill, over characteristically flat beds and through vertical concrete banks. These ‘channelized’ streams, as well as flat terrain, such as parking lots, do little to abate the flow of water. Consequently, water runs fast through human-managed watersheds causing erosion, road damage, and flooding.

In natural watersheds, the flow of water is slowed by plants, collected by ponds and reservoirs, and held deep underground. This produces a slow and steady flow of water throughout the landscape and provides plenty of watering holes where animals can gather and water-loving plants can thrive.

Natural watersheds can thus greatly improve the environment for people and nature. They produce clean bodies of water for people and animals, nourish a diversity of flora and fauna, and moderate the flow of water. Wilson has some recommendations for municipalities and individuals who want to work to create more naturalistic watersheds.

Part of the solution is to build swales that can capture and temporarily hold rainwater. According to Wilson, these reservoirs, often called rain gardens, can be planted with native, deep-rooted plants to maximize their ability to hold water.

Native plants can also be built in other parts of the landscape. A particularly effective place to plant is in parking lot flower beds as this can break up the flat terrain and interrupt runoff, soaking the water into its roots.

Wilson also suggests that communities de-channelize streams.

“Rivers and streams need room to spread out in a heavy rain,” Wilson explained. “That’s why they have a natural flood plain.”

We tend to think of rivers as static, unchanging features of the landscape. In reality, the breadth of a river and the path of its flow shifts throughout time. “Those flood plains occur over millions of years. We are only here long enough to see that little river. We don’t see the chaos or the creativity of the floods that formed the valley.”

When building our cities, we tend to build right along the banks and then come in after the fact to channel and pipe the unruly streams. But it may be wiser to look not at the river, but at the flood plain.

“In a lot of cities, you can’t build anything within 50 feet of the creek,” Wilson said. “But that’s really not enough. For wider creeks, it should be a minimum of 300 feet.”

Moving away from mechanized watersheds, made up of pipes and channelized streams, to something more natural, can provide communities with clean bodies of water and a flourishing natural environment. To make this transition, it’s important to recognize that rivers and streams are not the abiding features we often imagine them to be. We should aim to construct buildings and plant gardens that leave room for the water that flows constantly through the landscape, allowing it to shape and reshape our communities.